There are more than 5,000 chemicals in the man-made group known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). At times during an informal workshop on the topic late last week, it felt as if there were also thousands of questions surrounding PFAS.

The virtual gathering of more than 50 state agency personnel and academics from University of Wisconsin System schools shined a light on knowledge gaps, as well as energized opportunities for collaboration to move forward Wisconsin’s PFAS research agenda.

Amy Schultz, environment researcher for the University of Wisconsin-Madison-based Survey of the Health of Wisconsin, summed it up for most participants when she said points of collaboration “span all the worlds. And, collaboration is necessary.”

All the worlds she referred to were the four areas around which the workshop had been organized:

- Environmental contamination by PFAS. PFAS has been found in surface and groundwater, rain, air, soil, fish and wildlife.

- How PFAS moves and how it persists in the environment. There are 80 known sites of contamination in the state, which is almost certainly not a finite number.

- How PFAS should be dealt with once it’s discovered. There was uniform agreement among workshop attendees that there needs to be a way to sequester PFAS, but how? PFAS can also be removed from water and disposed of under proper conditions, but this can be expensive.

- The effects of PFAS on people. Studies have shown PFAS can increase cholesterol levels, decrease the efficacy of vaccines and—for pregnant women—cross the placenta and also be transmitted through breast milk. PFAS has been linked to cancer, osteoarthritis, ulcerative colitis and thyroid disease.

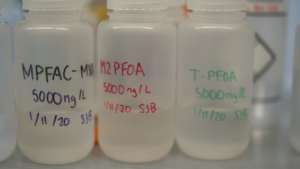

A recent PFAS workshop identified many knowledge gaps and potential collaborations between state agencies and scientists. Workshop organizers committed to the release of more information to set a research agenda. Photo: Bonnie Willison, Wisconsin Sea Grant.

The workshop hosts—Wisconsin Sea Grant, the University of Wisconsin Water Resources Institute and the Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene—laid out goals for the workshop: identifying what is known about PFAS; targeting knowledge gaps; fostering working relationships between staff at the departments of Health Services, Natural Resources, and Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection and the research community to accomplish further work; and charting next steps.

At the conclusion of the two 4-hour sessions that saw speakers, technical panel discussions and breakout sessions, that tick list seemed complete. The group plans to continue informal conversations to formulate research needs and share research findings and resources that will lead to actions that protect Wisconsin’s environmental resources and public health from PFAS as they are present in numerous products of everyday life.