The business end of a sea lamprey. Image credit: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

The New York Times recently published an article about eating invasive species as a means of control. It reminded me of a demonstration project we undertook when I worked at Minnesota Sea Grant in 1996. We received money from The Great Lakes Protection Fund for two years to study the overseas market potential for Great Lakes sea lamprey.

I’m sure you all know that lamprey, with their penchant for sucking blood, are a parasitic exotic species that entered the Great Lakes and almost wiped out the Great Lakes fishery by the 1940s. This led to a control program coordinated by the Great Lakes Fishery Commission that is ongoing even today. Every year, the commission’s various lamprey control programs cost millions of dollars. Sea lamprey are clearly still an enduring threat.

In the mid-1990s, the commission’s lamprey control program routinely landfilled thousands of female lamprey they trapped. At that same time, lamprey populations in their native countries like Portugal and Spain were becoming decimated due to overfishing and habitat loss. This was an issue because lamprey were/are considered a culinary delicacy in Portugal and Spain. Like the lobster aquariums found in American restaurants, Portuguese restaurants offered tanks of sea lamprey where people could pick their dinners. Exclusive and expensive clubs even formed around lamprey consumption.

Jeff Gunderson, the fisheries and aquaculture specialist with Minnesota Sea Grant at the time, took an idea from a University of Minnesota food professor and the extension leader at Minnesota Sea Grant and turned it into a project to find a use for the excess, unwanted Great Lakes lamprey by seeing if chefs in Portugal and Spain would find them as palatable as their native lamprey. He set up a team that included a professor in Portugal who would conduct market testing, University of Minnesota experts, a NOAA international marketing expert, and a fisheries biologist.

My job was to garner visibility for the project and its results. When Jeff first described the project to me, one of my first questions was whether the lamprey had been tested for mercury. “I don’t want to promote something that’s going to contaminate people,” I recall saying. He assured me the lamprey had been tested and were within U.S. standards. But what I didn’t know at the time was that only a small sample of lamprey were tested. (More to come on this later.)

To figure out my publicity strategy, I consulted a couple of my news reporter friends. I think it was Mike Simonson, the well-known and now dearly departed Superior bureau chief for Wisconsin Public Radio who said, “You gotta have a taste test!”

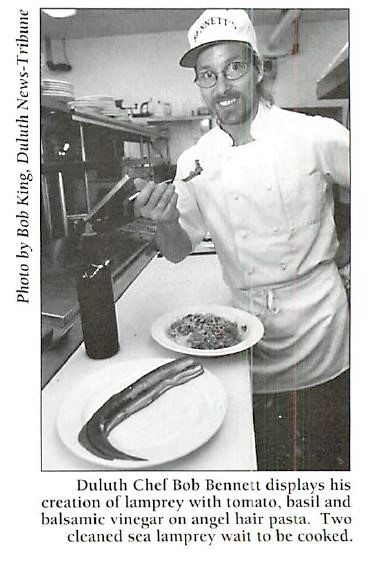

That sounded like a capital idea, so my first step was to find a local chef willing to cooperate. I approached my favorite restaurant, Bennett’s Bar and Grill, run by Bob Bennett. This “forefather of contemporary cuisine in Duluth” was game.

The Portuguese professor had given me several traditional sea lamprey recipes, at least one of which involved using lamprey blood. Ewww. Anyway, I showed these to Chef Bennett, and we came up with a taste-test plan. He would prepare two traditional recipes and create two of his own. Gunderson talked the original Lou of Lou’s Fish House in Two Harbors into smoking some lamprey for the taste test, as well.

The Portuguese professor had given me several traditional sea lamprey recipes, at least one of which involved using lamprey blood. Ewww. Anyway, I showed these to Chef Bennett, and we came up with a taste-test plan. He would prepare two traditional recipes and create two of his own. Gunderson talked the original Lou of Lou’s Fish House in Two Harbors into smoking some lamprey for the taste test, as well.

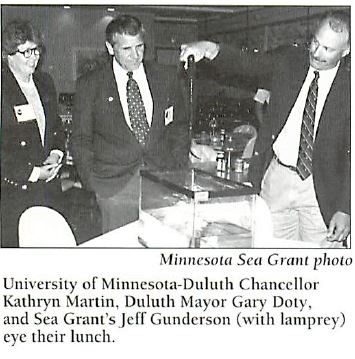

Next, we had to find some brave lamprey consumers. Somehow, I managed to convince the Duluth mayor (Gary Doty) to participate along with the University of Minnesota Duluth chancellor (Kathleen Martin). Several members of our Sea Grant Advisory Committee also agreed as did a freelance graphic designer who worked for us, a congressional office manager and the Minnesota Sea Grant director (Michael McDonald),

We held the lamprey taste test at Bennett’s restaurant, which was on Superior Street in downtown Duluth. Eight intrepid tasters were seated at a long table facing into the room so that reporters could easily see them and ask about their reactions to the food. We gave them a rating form. We also provided an aquarium with several lamprey in it, just to add to the room’s ambiance, and the smoked lamprey and some crackers for snacks.

Simonson was right about the lure of the taste test. We were mobbed by local reporters, both print and broadcast. Reporters from the Twin Cities even made the trip up north for it. The resulting stories went everywhere, even internationally. The Associated Press picked up the print story, and Gunderson said he talked to someone who saw it on a television station in Seattle. The story eventually made it into Newsweek and The New York Times.

Back in my office after the test, I received a phone call from the daughter of a Portuguese immigrant in Boston who saw the news stories and wanted to know how to obtain lamprey. She told me lamprey was a traditional Sunday dinner in Portugal, just like American pot roast. Her father was so excited when he saw the news, he implored her to find out more. I had to give her the disappointing information that lamprey were a regulated invasive species without a commercial source yet.

The highest rated dish was Bennett’s own lamprey stew with garlic mashed potatoes, rated 4.5 out of a possible 5. The smoked lamprey came in second, earning 3.7 out of 5. The taste of the lamprey came out more strongly in the traditional dishes, which did not suit these American taste-testers.

The highest rated dish was Bennett’s own lamprey stew with garlic mashed potatoes, rated 4.5 out of a possible 5. The smoked lamprey came in second, earning 3.7 out of 5. The taste of the lamprey came out more strongly in the traditional dishes, which did not suit these American taste-testers.

I ate both the lamprey stew and the smoked lamprey. I enjoyed the stew, although the chef forgot to take out the lamprey’s cartilaginous backbone (called a notochord), which made it a bit crunchy for my taste. I bet if he had removed the backbone, the dish’s ratings would have been higher. The smoked lamprey tasted rather like any kind of smoked fish – very good!

The taster’s comments included: “Surprisingly good. Try selling it without telling people what they are eating. It would be better.” And, “I would not order this out, but Bennett’s dishes were by far the best.”

More extensive taste tests were run in Porto, Portugal. Eight restaurants with lamprey-cooking experience, two homemakers and 16 individual taste testers participated in two studies. The restaurant chefs were asked to rate how the lamprey looked while alive, how they cooked compared to Portuguese lamprey, how they smelled/tasted/looked after cooking, how the lamprey tasted to them, and how their clients or family members liked them.

Overall, the Portuguese taste testers enjoyed the strong flavor and firm texture of the lamprey, noting the lamprey had a pleasant “turf” taste and was less soft and fatty than Portuguese lamprey. (A turf taste refers to an earthy flavor, somewhat like mushrooms or liver.) They rated the flavor 4.5 out of 5 – a definite win.

During the second year of the project, more lamprey were shipped to Spain for taste tests. The results weren’t as glowing, perhaps because only frozen and canned Great Lakes lamprey were shipped instead of live wriggly ones. The Spanish testers liked the texture and that some contained eggs. Yes, lamprey are a delicacy in Spain, but lamprey caviar takes it to a whole other level.

The death knell for this innovative program came from subsequent contaminant tests on the lamprey. The Great Lakes lamprey contained mercury levels that were too high to meet European Union standards. They tested at 1.3 ppm for mercury. The EU standard at that time was 0.3 ppm. This information came too late for our taste testers, but hopefully, one meal of lamprey was not detrimental. I certainly didn’t feel any ill effects.

Gunderson summed it up like this: “At least we have an answer to the question that has been debated for nearly 40 years. Yes, Great Lakes lamprey are marketable in Europe. Because of current control programs and experimental programs, a commercial harvest of lamprey would not have been a priority even if mercury levels were acceptable. But given time, a commercial harvest could fit into lamprey control and management. Lamprey are here forever and who knows if the funding for lamprey control will last that long. If funding ever does wane, let’s hope it’s not before mercury levels decline to acceptable levels so that lamprey harvest can be evaluated as part of a low-cost management program.”

That was almost 25 years ago. A Lamprey and Rice Festival is apparently held in Portugal each year, so it still must be popular, but I fear that the people who used to love eating them for Sunday dinner are aging out of this world.

Unfortunately, mercury levels in Great Lakes lamprey are still high. According to a 2018 study by the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission and the University of Wisconsin, levels in adult lamprey were still beyond that deemed safe for human consumption.

In any event, this project was one of the highlights of my career. It seemed like a win-win idea: The U.S. could rid itself of an expensive invasive species, and European diners could eat a traditional and much longed-for dish. Yes, I promoted something that could have contaminated people. But I did a darn good job of it.