They came to the harbor regularly, every evening, drawn by some need. It was as if the water floated off and set sail thoughts that had grown stagnant on dry land, and gave to their bodies even some sort of physical relief. – “To the Lighthouse” by Virginia Woolf

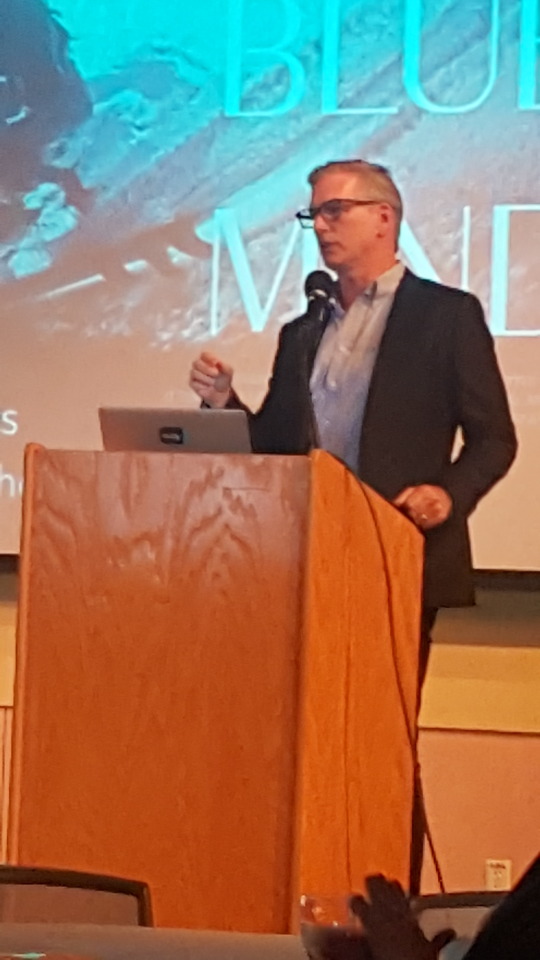

Earlier this month, more than 275 water managers, educators and scientists gathered for the St. Louis River Summit at the University of Wisconsin-Superior, just a mile away from the water that was their topic. The keynote speaker, Wallace Nichols, urged them to think about water in a different way than usual for a scientific conference.

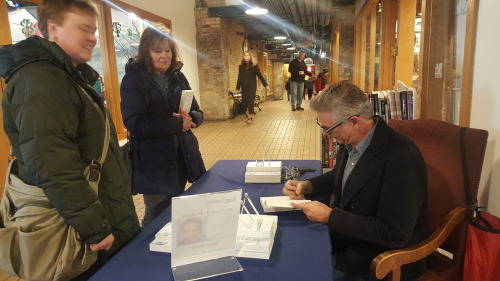

Nichols is the author of “Blue Mind: The Surprising Science That Shows How Being Near, in, on, or Under Water can Make you Happier, Healthier, More Connected & Better at What you do.” He’s also a sea turtle biologist and water advocate.

He opened his talk, entitled “The Blue Mind Community,” with these words:

“We often separate the science and the technical from the emotional and the spiritual. My simple message is to bring them closer together.”

Nichols said that when he’s sitting next to someone on an airplane, as a conversation-starter, he likes to ask, “What’s your water?” “People have an incredible array of answers to that simple question,” he said, “ranging from the bodies of water they currently live near and work for, to the dew on the plants in the morning, or the water that’s in their food.”

With a mixture of personal stories and research results, he described how important water is to people from emotional, psychological and spiritual standpoints. “Just to be quiet in or near the water. To learn a new activity, learn to surf or to swim – those are very often the highlights of our childhood or adulthood,” he said.

Nichols credits a 10-day stay in the Apostle Islands when he was in high school as sparking his interest in marine biology. “It’s where you feel like the best version of yourself. You are surrounded by nature, you’re in the elements. You’re where you should be.”

He’s taking this psychological route to water conservation as a way to enhance current traditional efforts. “Of course, the economics of conservation are important, but we will never have the funding we need to do the work we know we need to do,” Nichols said. “That’s a bold and sobering statement. So what are we going to do about it? We’d better utilize all the tools in the toolbox, including the power of emotion.”

To better understand water from a psychological standpoint, Nichols needed to familiarize himself with neuroscience. He spoke to neuroscientists on his campus and listened to audio classes on headphones while he was swimming. He explored studies that link exposure to water and improvements in health and functioning, and he designed his own surveys.

“We are in what I refer to as the golden age of neuroscience. We are also in the golden age of aquatic exploration. When those two realms are combined, fantastic things can happen,” he said. “As scientists, decision-makers, as leaders, as managers, we need to bring this science to the table and stop leaving it out of our public speaking, our reports, our communications, our films and our mission statements.”

He described how the same neuroscience techniques used for marketing products can be used in a transparent way for conservation purposes “to use the right words and images to get people’s attention, to move toward our goal.”

The Blue Mind Nichols talks about in his book relates to how being by or in water can calm people and make them more creative. This is opposed to the Red Mind, which he says occurs when people are anxious. Many studies have shown how green space in communities (forested areas) are good for people. “But we also know that blue space works as well, or better,” he said. “And when you combine green and blue, it’s the best … . These are old, ancient traditional ideas. I’m not saying anything new.”

Nichols encouraged the conference attendees to include the emotional benefits of water in their reports and budget justifications, and to prioritize the cognitive, psychological, social and spiritual benefits of healthy waters along with the ecological, economic and educational benefits.

“What if we did that? Perhaps our jobs would get a little easier,” he said. “Perhaps we would have even more support for the work we are doing to protect and restore our waterways.”