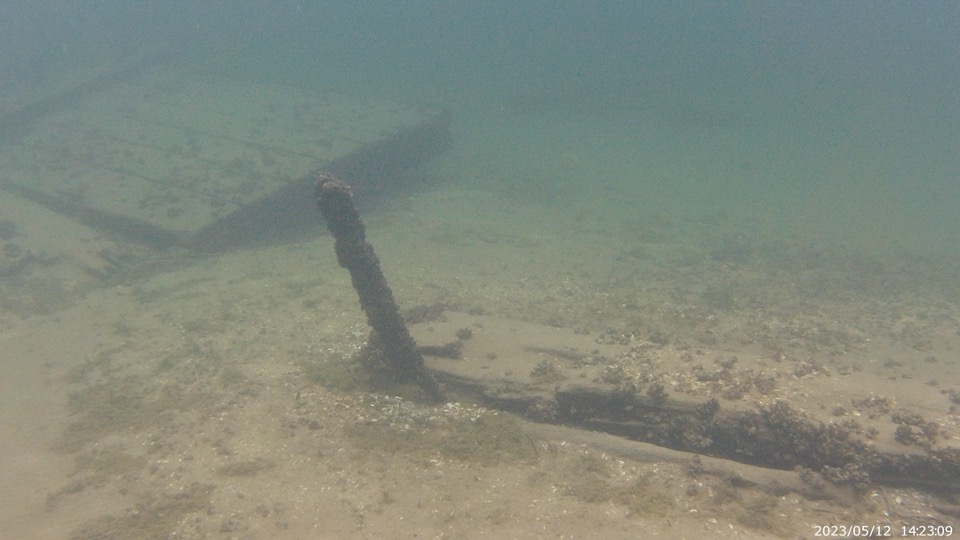

A diver measures the wreck of the Silver Lake, a double centerboard scow schooner. Photo credit: Wisconsin Historical Society

When sailing ships were the primary mode of transportation across the Great Lakes in the mid-1800s, there floated an odd duck: the double centerboard schooner.

Equipped with not one but two centerboards, these ships could haul lumber more quickly across Lake Michigan. The extra centerboard, a fin-like appendage that could be lowered from the bottom of the boat, enabled a more direct and less zig-zaggy route when sailing into the wind.

It was a rare feature on a Great Lakes ship and a short-lived one. Wisconsin Historical Society Maritime Archaeologist Tamara Thomsen said double centerboards faded from use by the 1870s, and many questions about their evolution and decline remain. But with grant funding from Sea Grant, Thomsen has been working to piece together the life history of these unusual vessels.

“We’re looking for these crumbs of evidence that are sort of scattered all over the place,” said Thomsen.

One of those places? The bottom of Lake Michigan.

Diving for answers

Maritime archaeologist Tamara Thomsen is completing a Sea Grant-funded research project on double centerboard schooners. Submitted photo.

For the past two years, Thomsen and a team of volunteer scuba divers have been busy resurveying the six known double centerboard schooner shipwrecks in Lake Michigan: the Boaz, Emeline, Lumberman, Montgomery, Rouse Simmons and Silver Lake. The team collected data on construction features, such as the location of centerboards, and took photos and footage that will be used to create 3D models of the wrecks.

“It’s a combination of photography, videography, photogrammetry [calculating measurements from photos], and then also … engineering drawings, which we create on the bottom,” said Thomsen. She also emphasized that the data her team collected is, in fact, the only way to understand how these ships were built.

“Vessels that were constructed in the 1800s were very, very rarely constructed by blueprint, and those blueprints do not exist today,” said Thomsen. “So, our understanding of how they were constructed and how this evolution of construction happened is all through the archaeological record.”

While resurveying the wrecks, Thomsen also positively identified the wreck of the Emeline (previously known as the Anclam Pier wreck), and she successfully listed both the Emeline and Boaz wrecks on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Horseshoe Island wreck. Photo credit: Bob Jaeck

Identifying the Emeline wasn’t the only thrill of Thomsen’s field research. The lake held another surprise: an undiscovered wreck.

While attending one of Thomsen’s training sessions for divers interested in surveying wrecks, volunteer Bob Jaeck alerted Thomsen to unidentifiable debris he encountered off Horseshoe Island in the bay of Green Bay. Having finished training early, Thomsen took the group to check it out.

It didn’t take long to figure out what they were looking at. There, submerged in the sediment, was another double centerboard schooner—the seventh in the state. The discovery was a high point for Thomsen.

“That was pretty cool,” she said.

So far, the identity of the vessel remains a “complete mystery.” Thomsen noted that there’s no recorded wreck at this location, but they’ve got a shortlist of ships lost in the general vicinity to guide their investigation.

A different kind of immersive research

When Thomsen isn’t diving into shipwrecks for her research, she’s diving into the archives. Much of her work on double centerboard schooners is, what she calls, “searching for breadcrumbs” in old ship papers.

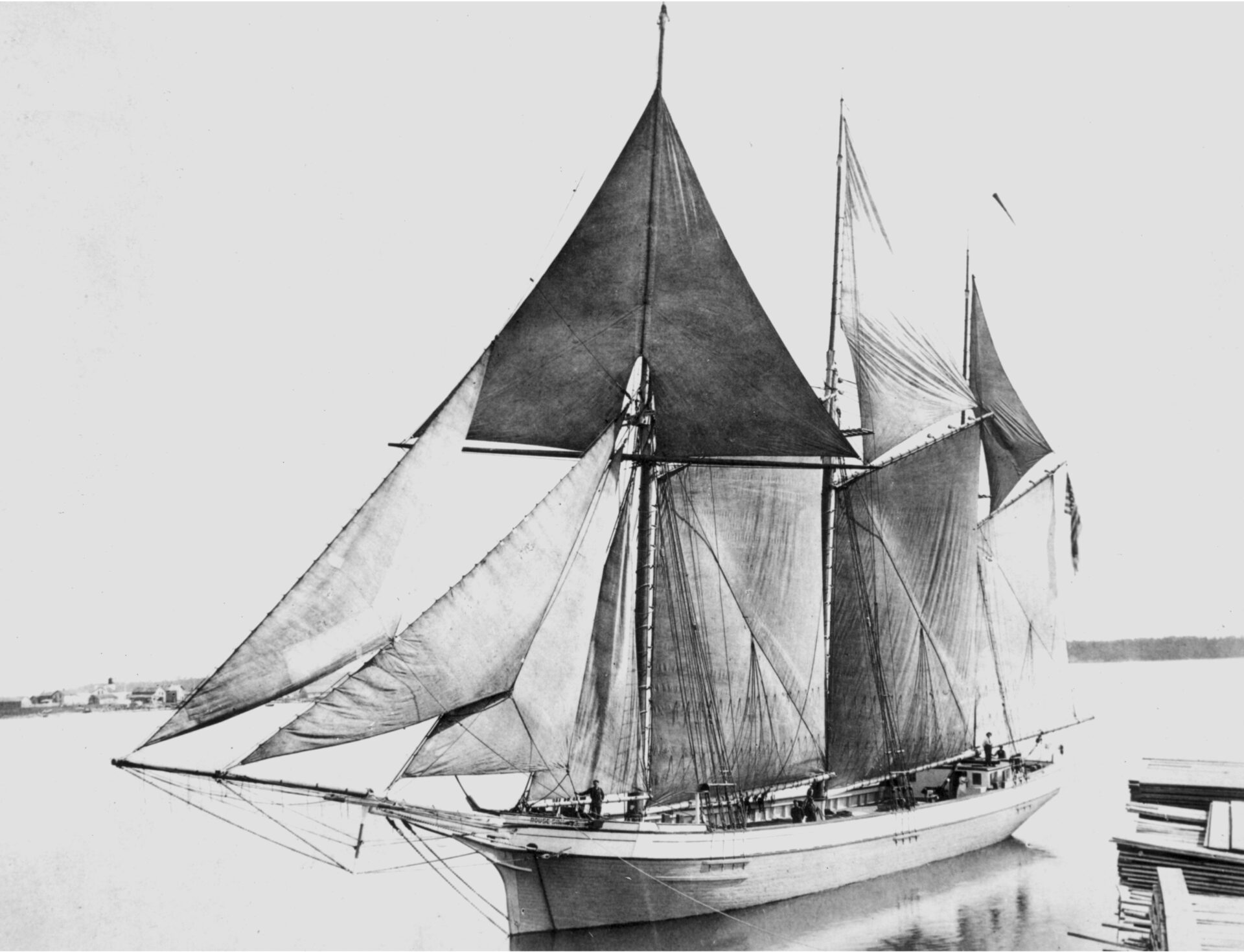

The Rouse Simmons, a double centerboard schooner that transported lumber across Lake Michigan. Photo credit: Wisconsin Historical Society

Finding documents about the construction and eventual decline of double centerboards on the Great Lakes proved challenging. One roadblock? Registration documents for ships didn’t record anything about centerboards.

“So, you’re looking for scraps of information that might appear in newspapers,” said Thomsen, or notes from shipyards that repaired damaged double centerboards.

Thomsen did find clues in the Rules of Construction, a government document that regulated the construction of ships. The first edition published in 1855 made no mention of double centerboards, but the 1876 version did, saying “no vessel of the first class should have more than one” centerboard.

“First class” refers to how vessels were insured: the lower the class, the less money you received if your ship was in an accident.

“So, your insurance value on your vessel decreased if you had a second centerboard,” said Thomsen.

Why the downgrade? The additional centerboard, it turns out, was risky. It structurally weakened the ship by putting a lot of pressure on the keel—or the backbone—of the vessel. An influential Wisconsin shipbuilder at the time, William Bates of Manitowoc, also argued it was unnecessary. Ship builders could make more structurally sound changes, like lengthening the first centerboard, to mimic the effect of having the second.

Thomsen believes Bates’s vocal dislike of double centerboard schooners—he wrote letters advocating insurance companies downgrade the rating—led to the ship falling out of favor on the Great Lakes. But no evidence has been definitive.

Histories, like shipwrecks, sometimes exist in fragments.

A shipshape team

As one of two maritime archaeologists with the Wisconsin Historical Society, Thomsen is busy traveling across the state from April to November surveying newly reported wrecks. It’s a big undertaking—one she accomplishes with a team of skilled volunteers.

Two divers take measurements of the Emeline shipwreck. Photo credit: Wisconsin Historical Society

Thomsen has long-standing partnerships with the Wisconsin Underwater Archaeology Association and Great Lakes Shipwreck Preservation Society to train 10 to 12 volunteer divers how to survey shipwrecks. Last spring, she held a workshop at a shallow-water wreck, where she taught participants how to draw vessels to scale and take scientific photos and video. Their skills are vital to the marine archaeology enterprise in the state.

It was a volunteer, after all, who tipped off Thomsen to the Horseshoe Island wreck.

“We would not be able to do the amount and definitely the quality … of work that we do without the assistance of these volunteers,” said Thomsen.

In addition to shipwreck survey trainings, the grant also supported outreach and education efforts. Thomsen was able to bring on maritime archaeologist Jordan Ciesielczyk-Gibson to adapt online educational activities about shipwrecks to in-person programming for kids. The “grab bag” for facilitators included a game with Great Lakes basin map, 3D-printed boats, puzzles and more.

Ciesielczyk-Gibson also co-created the first Wisconsin maritime educators workshop with Anne Moser, Wisconsin Sea Grant education coordinator, this past summer. The event gave educators the opportunity to network and share ideas for getting young people excited about Wisconsin’s rich maritime history.

A history, as evidenced by Thomsen’s research on double centerboard schooners, that continues to take shape.

Thomsen said she’s fortunate to do the work she does. Underwater with a shipwreck, she feels reverence.

“These are places of great tragedy and loss, and sometimes people died on them,” said Thomsen. “To be tasked with protecting them is just such an honor.”