Ask Jim Lubner about his 33-year career as a boating safety and education outreach specialist at Wisconsin Sea Grant (and what led to those years), and he’ll tell you about Lake Michigan.

“Living in the Bay View area of Milwaukee, I’m never very far from Lake Michigan. I see it on a regular basis and spend many hours each year on its waters as well. I consider it very special and am always reminded of the significant part it has played in my life and that of my family. I’m thankful for all of those people, experiences and opportunities,” he said.

He grew up on a farm in Sheboygan County, which borders Lake Michigan, spending his high school and college years in Catholic school and the seminary. He enjoyed fishing in Lake Michigan and in the fairly large lake across the neighbor’s field using a small aluminum boat you could throw in the back of the pickup truck.

While fishing continued to hold its appeal, Lubner realized the seminary wasn’t the right direction for him and he secured a position at a Catholic middle school, teaching science and math for three years. It may not have been his ideal job.

“I won’t say that I was necessarily good at it, but it was an early opportunity to get involved in education. In the back of my mind I really knew that if I was going to shift away from the seminary that I was going to pursue education, likely in the sciences,” he said.

And pursue education he did. Lubner received a master’s degree in zoology and a Ph.D. in biological sciences from the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. He became a teaching assistant during his master’s program, as most graduate students do, until another student suggested he find a program with the resources to support him in other ways. The Center for Great Lakes Studies was the only program that came to mind, and Lubner secured a position there.

During a graduate student seminar at the Center for Great Lakes Studies, Lubner was approached by a Ph.D. student with ship time who was studying pelagic zooplankton. He proposed that Lubner take on studying the benthos, allowing them to share the work of collecting samples and the ship time. Sea Grant was funding that project and Lubner joined right in.

During a graduate student seminar at the Center for Great Lakes Studies, Lubner was approached by a Ph.D. student with ship time who was studying pelagic zooplankton. He proposed that Lubner take on studying the benthos, allowing them to share the work of collecting samples and the ship time. Sea Grant was funding that project and Lubner joined right in.

Sea Grant was funding some projects that supported his master’s degree, and he was encouraged to submit a proposal for his Ph.D. project, which was funded for several years.

Lubner assumed he was headed for the classic tenure-track academic position, but nothing seemed to fit. When a position became available at Sea Grant, he decided to give it a try.

“Opportunities present themselves and sometimes you take a leap,” he said. “I have no idea what the heck I’m doing, but sometimes, it turns into something that maybe soon or maybe way far down the road and you say, ‘Geez, I’m glad I did that.’”

That opportunity turned into a 33-year career at Sea Grant, specializing in boating safety and, most of the time, education, even including an adjunct faculty position.

An early emphasis of the job was boating safety. Kim Bro (the Sea Grant field agent in the Lake Superior office) suggested partnering with an established organization with a solid track record, so Lubner joined the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary in 1979. He taught courses in boating safety to several thousand adults and young people and continues his membership in the Coast Guard Auxiliary to this day.

Over the course of working with the Coast Guard, Lubner started a pilot program for charter boat operators to help them with licensing and other requirements and wrote up a guidebook published by Sea Grant. Today there is a national-level program for charter boat captains (not as a direct result of the earlier program) that Lubner remains involved with.

Another long-lasting relationship resulted from an invitation to join the local emergency planning committee, which oversees the planning for spills of hazardous materials within a county. He’s been on that committee in Milwaukee county for 32 years.

For the education side of the position, there was a project already underway in Milwaukee when Lubner first accepted the job in 1977. The project focused on kids in Milwaukee and was funded by Sea Grant and led by a professor from the UW-Milwaukee Department of Curriculum and Instruction along with a UW Extension staff member with close ties to the inner city community in Milwaukee. The program ran its course, but it gave Lubner an inroad that turned into an adjunct position in the School of Education, Department of Curriculum and Instruction.

Then the Reagan era arrived, and many entities shifted their focus away from education. The same was true for Sea Grant’s national priorities. At one point Lubner received a letter from Bob Ragotzkie, the Sea Grant director at that time, stating very clearly that education was no longer in his job description.

Lubner said, “It is to his everlasting credit that Al Miller [the Sea Grant assistant director of outreach at the time] found creative ways to involve me in education, knowing full well that it was officially not my job description.”

As the interest in education projects started to rise again with a different administration, Lubner discovered that what the program needed was not better education proposals to biennial Sea Grant competitions but a better review process. Education projects can’t be evaluated fairly using the same criteria as research project.

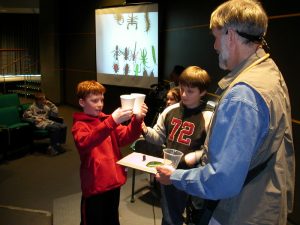

Lubner with students at an education event in 2006.

Lubner said, “When you ticked off the boxes that a reviewer would tick off (related to an education proposal), there weren’t enough science boxes. So even if it was a good proposal, it didn’t rate as high as the science proposals.” He set to work creating a review process for education projects that resulted in the funding of many successful education projects.

In addition to his boating safety work and his role as education coordinator, Lubner served as an adjunct professor, largely teaching middle and high school teachers about Great Lakes, ocean and climate topics. He described two-week teacher trainings as “the most exhausting and exhilarating experience I ever had.”

In addition to his work as a Sea Grant educator, Lubner also taught a course called “Environmental Education for Teachers” at UW-Milwaukee that was a requirement for teacher certification in Wisconsin. The teachers who enrolled primarily taught middle school, but then UW-Milwaukee’s approach to teacher certification changed, resulting in more early-childhood majors appearing in his classes.

He was rather dismayed with this development, saying that they “scared the heck out of me because I didn’t really know anything about early-childhood educational principles and practices.”

He soon realized that he loved the enthusiasm and dedication of these teachers and the way their energy and knowledge influenced the interests of the kids. “Early childhood is really just about awareness,” he said. “It’s helping them make the connection they can make at that level so that five years from now, 10 years from now, the teacher in the classroom can help them make a higher-level connection.”

Lubner in 2011

Starting environmental education early can make all the difference. Lubner said, “I remember one young teacher who said, ‘I teach kindergarten. What can I do?’ And one of the other teachers looked at her and said, ‘I’m a middle-school teacher, and what you do for those young kids, that sets the tone for what they are by the time they get to me.’”

As Lubner looks back at what changed over the span of his career, he noted a couple of changes that have benefited education—an increased emphasis on accountability and an increase in enthusiasm for outreach. As government budgets became tighter, officials wanted to be sure their dollars were having the most impact. How can you ensure that the research you’re funding has a real-world impact? Outreach and education became important aspects of that accountability.

Lubner said, “When I was working, except for the last number of years, scientists did their work and assumed that somebody would recognize the value for policy decisions down the road. Then finally somebody figured out if we don’t get policy experts in there who can tell the political decision makers what the benefits are for their constituents and make these social connections, they won’t care about the science, no matter how good it is.”

He went on to explain that Sea Grant has always tried to serve as a bridge between scientists and the general public, and in the early days it was one of a very few organizations serving that purpose. He’s found that younger scientists seem to have more of a desire to reach out and get their message across to a wider audience, and he thinks the work that Sea Grant has done helped lay the foundation.

“To some extent we can take credit for showing the importance of [outreach]. It adds to the number of people who are actually doing it, which is a good thing,” he said.

In addition to his enduring roles at the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary and the local emergency planning committee, Lubner is well known for his work with the Lake Sturgeon Bowl. He brought the competition to Milwaukee—somewhat by accident. A group from the National Ocean Sciences Bowl requested a meeting with J. Val Klump, formerly associate dean of the School of Freshwater Sciences. Klump was unable to attend and asked Lubner to attend instead. Lubner, Klump and UW-Milwaukee formed a strong partnership with the national organization and created the Lake Sturgeon Bowl. The program allowed Lubner to work closely with the Bowl’s regional coordinators. He finished his Sea Grant career working with Liz Sutton of the School of Freshwater Sciences, regional coordinator for the Bowl, and he continues volunteer work with outreach and education activities in his retirement.

“I still have an office at the School of Freshwater Sciences, so when I do a tour, I tell people I’ve had an office in that building since 1977. They haven’t thrown me out yet,” he said.