Carp, Cats, Perch and Pearls: Wisconsin’s Unsung Commercial Fishery

Carp, Cats, Perch and Pearls: Wisconsin’s Unsung Commercial Fishery

By Sharon Moen

Wisconsin Sea Grant exists because the state’s boundaries include parts of lakes Superior and Michigan, which are viewed as inland seas by the U.S. government. Commercial fishing for food happens in these waters and Sea Grant works to help these fisheries succeed. However, there is another Wisconsin boundary where commercial fishing for food occurs – the one defined by the Mississippi River. This lesser-known fishery is also within WISG’s statewide purview.

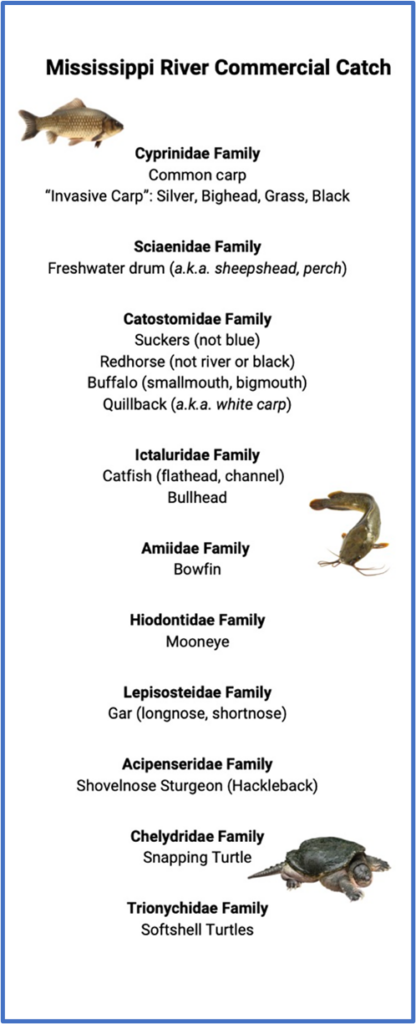

Commercial fishers of misi-ziibi (the Ojibwe word for Great River, the Mississippi) harvest an average of 3,000 tons of fish annually. This harvest makes up approximately 2% of the total inland catch in North America[1],[2]. Of the 119 species of fish swimming in the Upper Mississippi River, Wisconsin commercial fishers are permitted to harvest members of eight families of rough fish (see sidebar). Rough fish is a catch-all term for edible, non-sports species. Wisconsin commercial fishers can also harvest two types of turtles from the Mississippi.

During the summer of 2023, Wisconsin Sea Grant staff and summer scholars visited Mississippi River commercial fishermen to better understand their businesses and the fishery and to discuss ideas for amplifying seafood production across the state. Read on to learn what surprised the Sea Grant team and how Sea Grant is working to address a challenge shared by Mississippi River commercial fishers and their Great Lakes counterparts.

Surprise #1 – Common carp are truly common

Common carp, a Eurasian species intentionally introduced into North American waterways well over a century ago, dominates the Mississippi River catch (~37% of total weight)[3].

Mike Valley, owner of Valley Fish and Cheese and a fourth-generation fisher said, “I got into fishing through my father and my grandfather who were in the same business. In the smoked fish end of it, we do carp, buffalo, bullheads, catfish, sturgeon and perch. And out of all of those, the carp is the number one seller. Second probably is catfish.”

Back in 1880, Wisconsin fisheries managers and residents welcomed common carp. One might imagine them cheering when 75 of these fish were shipped from Washington, D.C., to the Nevin fish hatchery near Madison, Wisconsin. Little did they know what mayhem would ensue as the offspring of the 75 were scattered throughout the Midwest. Carp can thrive and prolifically spawn in practically all types of water. After arriving at Nevin, it took common carp less than three years to show up in the Mississippi River. [4]

There are four other non-native invasive carp that Mississippi River commercial fishers in Wisconsin are encouraged to keep: grass, sliver, black and bighead carp. These animals were introduced to the southern U.S. in the 1970s. The purpose of the intentional translocations was to manage algae, weeds and parasites in aquatic farms, canal systems and sewage treatment facilities. Echoing a host of nature horror movies and real-life disasters, they escaped into the Mississippi, pushed their range northward and established breeding populations.

Mike Valley, owner of Valley Fish and Cheese. Photo by Bonnie Willison

Surprise #2 – Cats can be huge

Arguably, there are two families of cats commercially caught in the Big Muddy: catfish (Ictaluridae) and buffalo (Catostomidae) (see sidebar). Both are native to the system and both can reach impressive proportions.

Valley said, “When I was 16 years old, raising nets with my father, we had two catfish in one net and they each weighed 96 pounds apiece. I haven’t topped that since. You know, we got a lot of catfish in the 60s and 70s. It’s nothing to get 25 a day over 25 pounds.”

Even though catfish can be big and plentiful, their market value plunged from $4.19/kg in the 60s to $1.07/kg in the 2000s.[5] Some suggest that the decline reflects the success of U.S. catfish farming. However, other species in the Mississippi River commercial catch also indicate that demand for these fish diminished over the past 50 or so years.

Catfish have no scales. Buffalo have giant scales. Within the Great Lakes commercial fishery, the scales of lake whitefish and cisco are sometimes referred to as fish glitter. Not so for buffalo and carp, which have scales so large they look like thumbnails in the bottom of a boat. Buffalo average about 26% of the Mississippi River catch[6] and make up the bulk of Jeff Ritter’s wholesale business, Ritter Fish. Ritter is a first-generation Mississippi River fisher who works with other commercial fishers to supply food to people in Minneapolis, Chicago and similar cities.

Ritter said, “We fish for buffalo, which is our number fish. But we basically harvest all rough fish. It’s a rough fish business, which is I guess is what you would call it.”

Surprise #3 – Sheepshead can be sold as perch

The common names of fish are varied and regional. For example, Aplodinotus grunniens goes by quite a few names, such as freshwater drum, sheepshead, silver bass, thunder pumper, gaspergou and perch. Yes: commercially harvested freshwater drum can be sold as perch. This encourages its consumption, particularly in big-city markets serving ethnic neighborhoods. Don’t be fooled, though. This species is very different from the fish-fry staple yellow perch, which Ritter reports are doing quite well. As someone who can’t seem to get enough of the water, he fishes for yellow perch recreationally in Ol’ Man River.

When asked how he likes to prepare fish, Ritter said, “Basically I like to grill fish or pan fry it. My favorite here on the river is yellow perch. We have a population that has exploded in the last ten years so we have some really nice fish. A good old sheepshead, a medium-sized sheepshead when it’s grilled is really tasty, too.”

Ritter also said that they do not see many non-target species in the nets because of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources’ mesh size restrictions. “Over the course of a year, I might see ten game fish total. We don’t harm our resource.”

A male sheepshead makes grunting noises by rubbing muscles along its swim bladder, causing it to vibrate. Native Americans strung together the freshwater drum’s large otoliths (granules of calcium carbonate) as necklaces or bracelets. There is some indication that this fish, with its big molar-like crushing teeth, may be learning to eat zebra mussels.

Jeff Ritter, owner of Ritter Fish, in conversation with Sharon Moen, food-fish outreach coordinator for Wisconsin Sea Grant. Photo by Jeremy Van Mill

Surprise #4 – Freshwater pearls and clam shells were big business

Once upon a time, the people of Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin,- lived in “the freshwater pearl capital of the U.S.” In these colorful years (1900-1920), clamming and button cutting was almost as important to the economy of the area as the fur trade had been.[7] A visit to Valley Fish and Cheese is also testament to this locally important industry. Artifacts from the clamming industry hang on the western exterior of Mike Valley’s processing building and, as a former clammer and adept storyteller, he is willing to share insights.

Valley remembers clamming in the 60’s, when the industry was in a revival. Then, the shells were being shipped to Japan to support the cultured pearl industry. Valley says that better pearls were being produced more quickly if the oysters were seeded with beads cut from Mississippi River clams. In the summer of 1966, 600 tons of shells were shipped out of Prairie du Chien.

Back in the day, though, buttons were the bread-and-butter of the industry. The high-value product was freshwater pearls. Freshwater pearls take on the color of their mothershells, which can range from pink to shades of blue, green and lavender. At one point, there were 27 freshwater pearl buyers in Prairie du Chien alone.[8] Summer tent cities involving entire families would line the riverbank while floating grocery stores would ply the water selling supplies.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources reports 39 species of mussels (commonly called clams) found along the Wisconsin portion of the Mississippi River. Their distribution varies and some are achingly rare. Most freshwater mussels can’t go it alone. They need particular fish or salamander hosts for their parasitic young (glochidia). To wit: Only gars function as hosts to the most valuable of all freshwater mussels: the yellow sandshell. This species was used for top-grade buttons, pearl handles for knives and similar artifacts.

Jeremiah’s Bullfrog Fish Farm. Photo by Bonnie Willison

A common conundrum: Where’s the workforce?

“There’s room for up-and-coming fishermen,” said Ritter. “If you have a good work ethic and stick your nose to the grindstone, I think you can make a good living at it.”

Commercial fishing on the upper Mississippi peaked in the mid-1960s when the industry produced more than 6,000 tons of fish and generated about $9 million. Since that heyday, the number of commercial fishers plying the Wisconsin waters of the Mississippi has declined to a mere handful. Many are over 50 and thinking of retiring. At least one is 80.

Valley said he fishes five days a week when he has help but when Sea Grant visited, he was fishing two. “We have no problem selling our fish. The problem is making it, finding enough time and the help. That’s the number one problem, you know? I can only clean 400 to 800 pounds in a day, so that’s what I catch. I could set nets and catch two or 3,000, no problem.”

Fisheries managers agree that the Upper Mississippi River commercial fishery is stable and could support larger harvests.[9] The gear needed is unsophisticated: gill nets, trammel nets, hoop nets, and trot lines. And it is common for people to participate in the commercial fishery to supplement other incomes. So, if you know of a youngster who, like Ritter, has a penchant for playing in the mud, chasing turtles and catching bluegills, or like Valley, who simply loves being on a boat at dawn, there’s a career opportunity as a commercial fisher worth considering.

Both Ritter and Valley say that commercial fishing is in their blood. “It has been in my blood since I was a little boy,” said Ritter. “The Mississippi River is God’s country, that’s for sure. If I’m not working, I’m playing on it. I just fish.”

A new fisher will reap the benefits of a less polluted river but also one that is being increasingly used for recreation including party boats and sports fishing events. Climate change will continue to challenge the commercial fishing industry with variable water levels, flash floods, droughts, heat waves and sedimentation caused by erosion. Invasive species will continue to add to the complications.

Sea Grant’s visits with commercial fishers are generating momentum for future workforce development programs. Additionally, the exchange of information with business and rural communities is helping to build a more resilient food-fish industry and supporting the Wisconsin Idea that education should influence people’s lives beyond the boundaries of the classroom. Find some of the results of the Mississippi River interviews here:

- The Fish Dish podcast: https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/audio/the-fish-dish/michael-valley-mississippi-river-fisherman-and-catfish-fillets-with-lime/

- Wisconsin Sea Grant’s YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bNgh6tn5GEg

[1] Welcomme, R.L. ( 2011), An overview of global inland fish catch statistics. ICES Journal of Marine Science 68, 1751 – 1756 .

[2] Klein, Z.B., Quist, M.C., Miranda, L.E., Marron, M.M., Steuck, M.J. and Hansen, K.A. (2018), Commercial Fisheries of the Upper Mississippi River: A Century of Sustained Harvest. Fisheries, 43: 563-574. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsh.10176

[3] Ibid.

[4] The first records of common carp caught in the Mississippi River were from Hannibal, Missouri, and Quincy, Illinois in 1883. https://www.nps.gov/miss/learn/nature/ascarp_common.htm#:~:text=German%20and%20Scandinavian%20immigrants%20brought,and%20Quincy%2C%20Illinois%20in%201883.

[5] Klein et al. (2018).

[6] Klein et al. (2018).

[7] Temte, E.F., 1968, A brief history of the clamming and pearling industry in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. Seminar paper presented to the faculty of the graduate school, Wisconsin State University at LaCrosse.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Johnson, B.L., and Hagerty, K.H., eds., 2008, Status and trends of selected resources in the Upper Mississippi River System: U.S. Geological Survey, Upper Midwest Environmental Sciences Center, La Crosse, Wisconsin, December 2008, Technical Report LTRMP 2008-T002, 102 p., plus 2 appendixes.