Floods can be devastating for anyone who experiences one. Flooding impacts can be even more intense, however, for vulnerable populations. That includes people who live in poor housing conditions, lack transportation options, or possess limited English skills that would hamper their understanding of emergency messages.

Through funding announced June 23 by the National Sea Grant Office (NSGO), Wisconsin Sea Grant is working with nine communities in northeastern Wisconsin to strengthen their resilience to flooding events by looking at who lives in the most flood-prone areas of a city. Wisconsin Sea Grant is partnering with the Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission and Wisconsin Emergency Management on this effort.

In addition to the Wisconsin project, the NSGO and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Disaster Preparedness Program are funding two other disaster preparedness projects in Hawaii and Massachusetts. (Find more details about those projects here.)

Work on the new project, which begins this month and continues through summer 2024, builds upon earlier Sea Grant-supported work using the Flood Resilience Scorecard. The scorecard is a comprehensive tool that helps communities look at their level of flood preparedness through a variety of dimensions.

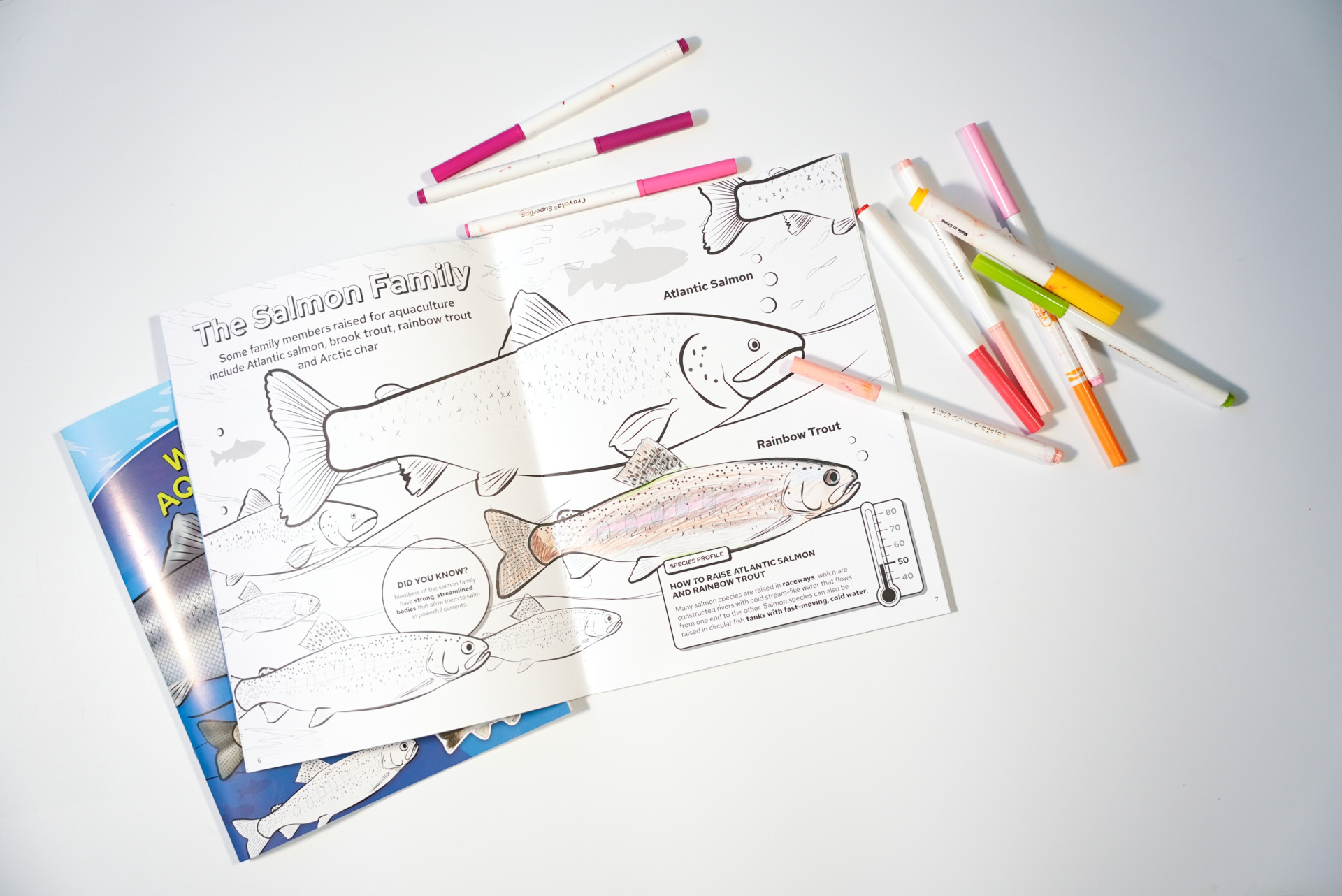

The Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission demonstrates its virtual site explorer at the Northeast Wisconsin Coastal Resiliency Open House in Manitowoc. (Photo: Adam Bechle, Wisconsin Sea Grant)

Jackson Parr, a Sea Grant staff member who served as the J. Philip Keillor Flood Resilience-Wisconsin Sea Grant Fellow from April 2021 to May 2022, will be a key player in this new effort. He worked extensively with the Flood Resilience Scorecard and Wisconsin communities during his fellowship, drawing on his dual master’s degrees in public affairs and water resources management.

While Parr’s fellowship work included both coastal and inland communities around the state, the new project will focus more specifically on the Lake Michigan coast from Sheboygan County northwards.

Parr will work with Wisconsin Sea Grant Assistant Director for Extension David A. Hart and Coastal Engineering Specialist Adam Bechle, as well as staff at the Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission, including Environmental Planner Adam Christensen.

Said Parr of his fellowship period, “Over the last year, I’ve worked with 16 communities…and we’ve identified some common gaps across all communities in terms of flood preparedness and flood resilience.” He found that no community had used spatial GIS technology to pinpoint where priority populations—those most vulnerable to flooding—live.

This kind of detailed, granular analysis can lay the groundwork for keeping people safer, especially because two places very close to one another can have very different flood risk. Yet doing this GIS work can be challenging to communities for a variety of reasons, such as a lack of resources or administrative capacity.

Said Parr, “These communities are doing a lot of good work in addressing some disparities, just not related to flooding specifically, because that gets into a narrower area than most communities have the capacity to do.” That makes the technical assistance offered by the newly funded project a welcome addition to what communities are already doing.

In addition to the GIS work, other aspects of the funded project include running the Extreme Event game in the communities. The game was developed by the National Academy of Sciences. Explained Parr, “It’s a scenario of a storm event, and random things happen throughout the scenario, and participants have to think how they’d respond. Then they do back-end reflection on that process.”

Game participants will include local officials and emergency management staff, but can also include residents who want to learn more about disaster preparedness and resilience in their community.

Said Christensen of the Bay-Lake Regional Planning Commission, “We’ll assist in outreach efforts to communities about participating in the game, screen for underrepresented communities in those areas, contact necessary stakeholders, attain Extreme Event Facilitator Certification to facilitate the games and provide local knowledge and mapping services for the team.”

Staff from Wisconsin Emergency Management will also get training in running the games, so they can do them in any Wisconsin community, giving the project a reach beyond the nine cities that are its main focus.

Participants in an East River Collaborative field trip learn about nature-based agricultural practices that slow down runoff and can help lessen flooding and improve water quality in downstream communities like the city of Green Bay. (Photo: Adam Bechle, Wisconsin Sea Grant)

A third outcome of the project will be implementing what’s known as the Plan Integration for Resilience Scorecard for participating communities. That assessment analyzes the variety of plans a community might have—from transportation to downtown revitalization to parks and recreation, for example—and helps them create consistent recommendations for floodplain management and disaster preparedness.

That helps avoid situations such as having one plan saying an emergency shelter should be located in a particular neighborhood, while another document prohibits that from a zoning angle, offered Parr as an example.

Taken together, the three main components of the project will help northeastern Wisconsin communities be better prepared to face challenges that may come their way, especially in a “perfect storm” event in which high Great Lakes water levels and extreme precipitation combine to cause significant flooding.

When asked about the biggest benefit of this project, said Christensen, “To me, the biggest benefit is the word ‘preparedness’—preparedness so that, when an extreme event occurs, the participating communities will be ready to react in an effective and efficient manner that saves lives.”

For more information about the project, contact Jackson Parr at jgparr@wisc.edu.