Wisconsinites depend on the state’s water resources. More than 26 percent of Wisconsin’s land area is within the Great Lakes Basin and more than 50 percent of Wisconsin’s population lives near lakes Michigan or Superior. These residents depend on the Great Lakes for their drinking water and other industrial and commercial uses.

As part of UW–Madison’s Aquatic Sciences Center, staff with Wisconsin Sea Grant and the Water Resources Institute are working to protect human health and Wisconsin waters by investigating per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) levels in lake water, game fish, maple syrup, and other harvestable goods.

This project was initiated by the Voigt Intertribal Task Force, a group composed of 10 of the 11 Ojibwe tribes that harvest from the Ceded Territories in parts of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan. The task force ensures safe harvest limits and is advised by the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission.

The three-year research project is tribally driven and it is already having wide-ranging impacts that will help people inside Wisconsin and beyond. In an article in “Environmental Science and Pollution Research,” the researchers outlined their findings regarding PFAS in maple sap and syrup. They found two types of PFAS in maple sap and 10 types in maple syrup. They are the first to publish the detection of PFAS in maple sap and syrup.

“The good news is that we detected very low levels of PFAS,” said Gavin Dehnert, emerging contaminants scientist with Wisconsin Sea Grant. “They are levels that are below drinking water standards and do not pose an immediate health risk to people.”

Dehnert suspects there are more types of PFAS in maple syrup than in the sap because the boiling process concentrates previously undetectable levels from the sap. He also noted that the PFAS could have come from equipment used during the syrup-making process.

Dehnert said the Voigt Intertribal Task Force has asked the team to expand the study by sampling maple sugar – a concentrated form of maple syrup – for PFAS and to try to determine where the PFAS contamination originated. It could be coming from the soil, groundwater, or precipitation.

The original project, “Quantifying PFAS bioaccumulation and health impacts on economically important plants and animals associated with aquatic ecosystems in Ceded Territories,” was funded by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Water Resources Research Act Program.

In addition to Dehnert, the project involves Jonanthan Gilbert with GLIFWC, Emily Cornelius Ruhs with the University of Chicago, Sean Strom with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, and Christine Custer and Robert Flynn with USGS. The maple sugar and PFAS source study is being funded by a Baldwin Wisconsin Idea grant.

Capturing tribal stocking and spearfishing traditions through video

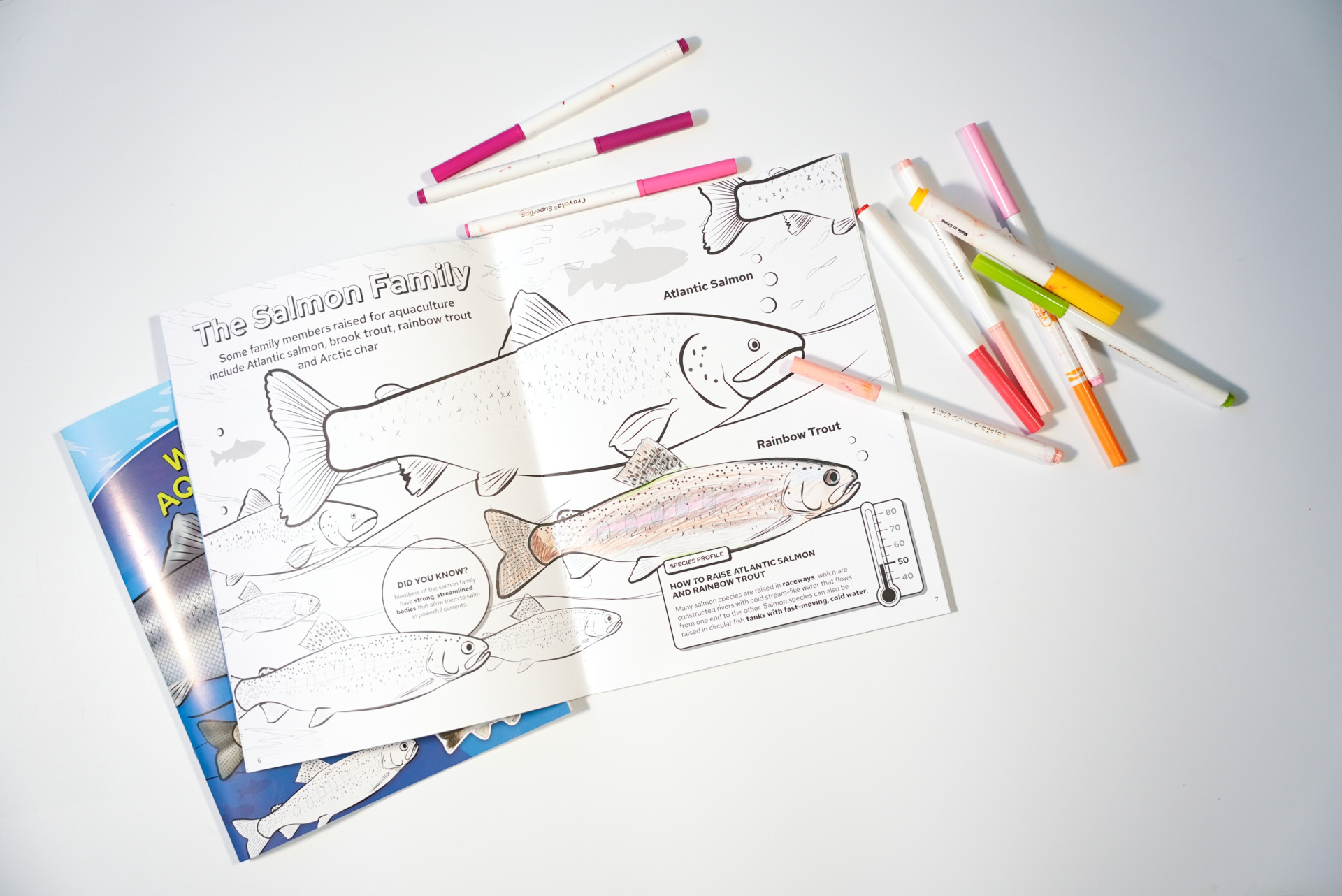

Another tribal entity, the St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin, is also working to protect a Wisconsin water asset – fisheries. They run an aquaculture operation in Gaslyn, Wisconsin, which they use to stock fish so that they can continue traditional practices like spearfishing.

Bonnie Willison, Wisconsin Sea Grant videographer, highlighted the tribe’s aquaculture facility and spring spearfishing practices in two videos.

The videos cover recent spearfishing history in the state, including more turbulent times in the late 1980s and early 1990s when protests at lakes being spearfished followed a 1987 ruling that reaffirmed tribal hunting and fishing in off-reservation Ceded Territory.

In response to the protests, a team of federal, state and tribal biologists formed the Joint Assessment Steering Committee in 1990 to analyze the impact of sportfishing and spearfishing on walleye populations. More than 20 years of research by the panel of fisheries biologists has shown that the walleye resource is not harmed by spring spearing, noting that only 9 percent of the tribal harvest is made up of females.

Jamie Thompson, air quality outreach coordinator for the St. Croix Chippewa Indians, said, “I don’t think that communities know that the tribes are also restocking these lakes along with the DNR. They’re always planning for seven generations after the generation here.”

Thompson explained that area lakes no longer favor walleye reproduction due to changing environmental conditions, so stocking is needed. “It’s very rewarding for me to be able to stock these fish into a lake and then five or eight years later, see my family and my kids harvesting those fish – whether it’s ice fishing, whether it’s on a line, whether it’s spearing. It’s not just benefiting my kids, it’s benefiting other tribal families as well as anyone who uses these area lakes.”

Don Taylor, natural resources manager for the St. Croix Chippewa Indians, added, “It’s very gratifying job for me. I like to see fishermen come off the lake and say, ‘Hey, you know, thanks for stocking the fish. We just caught our limit.’”

Each spearer that goes out is issued a permit by GLIFWC, which specifies how many fish they can catch and which species. Each lake has a different quota based on population estimates done by the state, GLIFWC and tribes.

Brad Kacizak, a game warden with GLIFWC, explained, “Usually, each person is allowed 15-20 fish. For most, this is their fishing harvest for the year. It’s not sportfishing – harvesting is what this is all about. It’s about putting food on your table, on your relative’s table and your neighbor’s.

“There can be a lot of misconceptions about what the tribes are doing out here,” Kacizak continued. “What people need to know is that this is the most scrutinized fishing season, definitely in the country, if not in the world. Because every single fish that comes out during the spearing season is accounted for. There’s another misconception that tribal members can spear as many fish as they want. That’s just simply not the case.”

“When we go out, we want to bless the lake for the fish that we take,” said Perry Staples, a St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin tribal elder at Big Yellow Lake near Webster, Wisconsin . “So, we offer our tobacco. This season is when we all get together. Our ancestors taught us spearing and so we’re following their trade. We’re honoring what they left us. We never want to lose this. We lost it once and it took a long time to get it back. We practice our rights and enjoy each other’s company.”