A new study has found that a plume of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from an industrial source has made its way into Green Bay, Lake Michigan, through the movement of groundwater.

PFAS are often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not readily break down in the environment. They have been used to make a wide range of products resistant to water, grease, oil and stains and are also found in firefighting foams, which are a major source of environmental PFAS contamination. The chemical compounds have been shown to have adverse effects on human health.

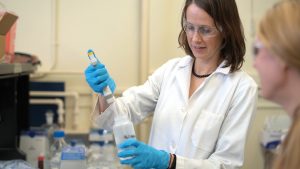

Christy Remucal with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and postdoctoral co-investigator Sarah Balgooyen published their work in the Dec. 27, 2022, issue of the journal Environmental Science & Technology, https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.2c06600 It was funded by a grant from the Wisconsin Sea Grant College Program.

“We used a forensics approach to investigate how the PFAS fingerprint from an industrial source changes after undergoing environmental and engineered processes,” Remucal said.

Researcher Christy Remucal in her lab on the University of Wisconsin-Madison campus is analyzing water samples taken from a known contamination site.

Researchers tracked the movement of PFAS through groundwater and surface water flow, as well as the chemicals’ presence in biosolids on land. Analysis of samples showed that, unfortunately, a large PFAS plume has moved into Green Bay, Lake Michigan.

Green Bay is one of the largest bays on the Great Lakes, an interconnected freshwater system providing drinking water for 30 million U.S. and Canadian residents. That makes it even more important for researchers to understand what contaminants are present and where they may have come from.

The source of this Great Lakes contamination has been traced to Tyco Fire Products. The company’s fire-training facilities in Marinette and Peshtigo have previously been identified as a source of PFAS contamination in groundwater and private drinking water wells in the area.

The forensic technique in this study used PFAS fingerprinting, a process that uses ratios of individual PFAS compounds to identify PFAS contaminants and their sources. In this case, the PFAS fingerprint in Green Bay is nearly identical to PFAS associated with Tyco and includes PFAS known to be active ingredients in firefighting foams. This fingerprinting method could be used to hold polluting companies responsible for the contaminated water, the researchers said.

The study also found that PFAS associated with the industrial facility are present in streams near some agricultural fields. The researchers believe this PFAS contamination may have come from the treated biosolids many farmers use to fertilize their fields.

Biosolids are the product of wastewater treatment and are rich in nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. PFAS in wastewater undergo extensive processing and some PFAS tend to concentrate in biosolids during treatment.

Remucal and Balgooyen determined that PFAS from biosolids can still mobilize after being spread on land. So, when farmers spread biosolids on their fields, PFAS can eventually make their way to adjacent streams.

Sarah Balgooyen is a postdoctoral investigator of PFAS, which is a group of man-made chemicals known for stain- and water-resistance, but also causes cancer in humans.

“Treated biosolids are commonly spread on fields all across Wisconsin,” Balgooyen said. “This information may impact how municipalities across Wisconsin and other states approach the use of biosolids as an agricultural fertilizer.”