Aquaculture Outreach and Extension Specialist Dong-Fang Deng discovered her love for fish in the long, winding gut of a grass carp.

“I didn’t think I was going to do any animal research,” said Deng, but a fish dissection at the lab she worked at while an undergraduate sparked her interest. The fishes she examined—the grass carp, tilapia and Japanese eel—all had differently sized intestinal tracts, with the grass carp having the longest. Talking with her professor about the diets of each fish, Deng had a realization: A “different gut [is] related to different food.”

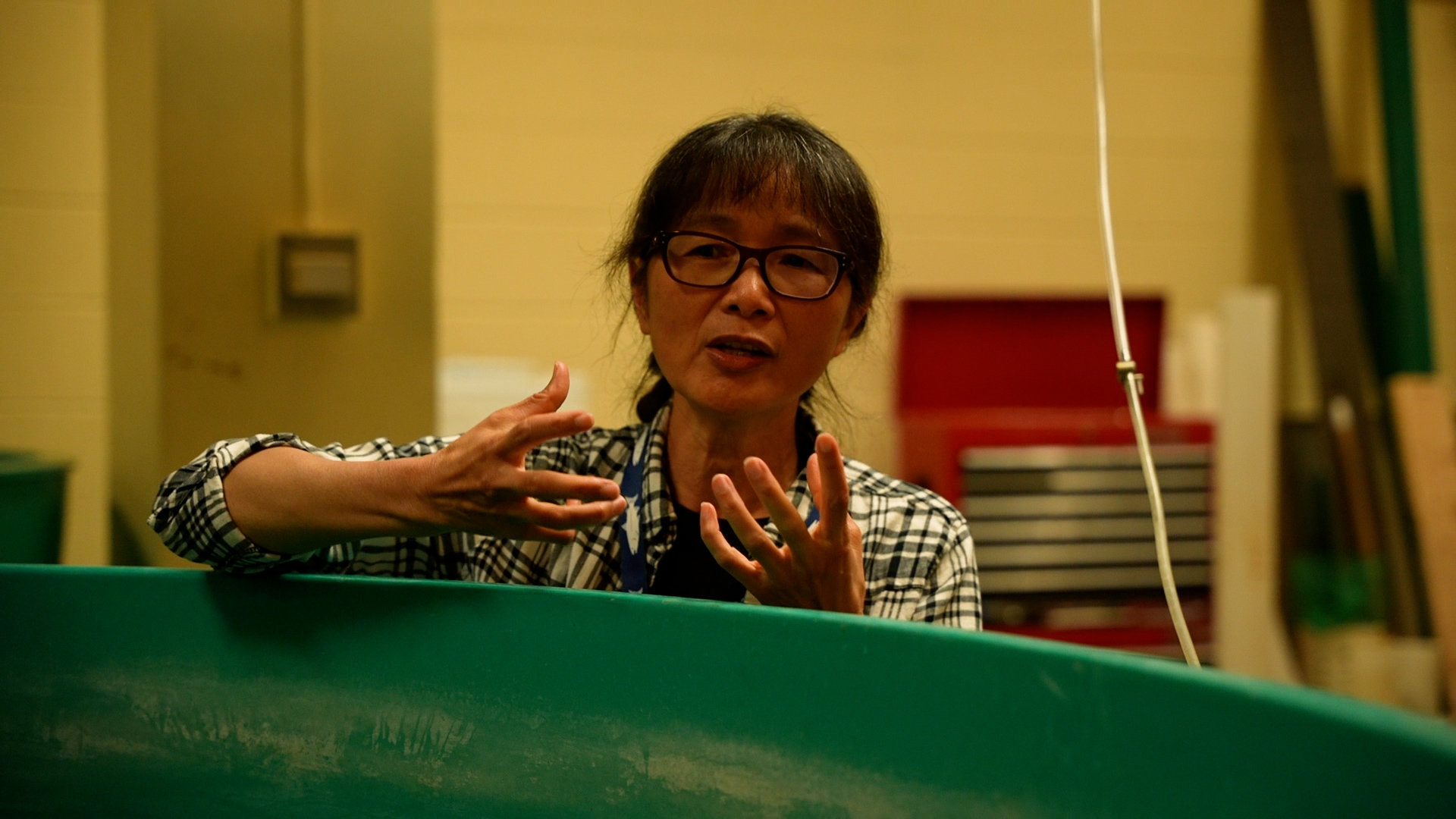

Aquaculture Outreach and Extension Specialist Dong-Fang Deng discusses fish nutrition in her lab at the UWM School of Freshwater Sciences. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Unlike tilapia or Japanese eel, grass carp are herbivores, and a long gut allows them to break down and absorb nutrients from plants. Deng credits her professor for encouraging her curiosity.

“I really appreciate that my professor worked with me,” she said.

Deng’s curiosity propelled her into a career in animal nutrition. In addition to her Sea Grant appointment, which began in February 2023, Deng is also a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences, where she researches and develops fish feed for the aquaculture, or fish farming, industry.

“We want to make the right diet for the right fish, that’s our general goal,” said Deng.

Formulating fish food, however, is no simple task. Different fish have different nutritional needs, and what works for one fish may not work for another. Take, for example, the yellow perch. Unable to tolerate the high-fat diets of rainbow trout and salmon, yellow perch will accumulate excess fat in their liver, which affects their metabolism. “If the liver isn’t functioning right, they can’t grow very well,” said Deng. “We need to figure out how to optimize the feed.”

Another consideration is the cost and availability of food. Aquaculture researchers have been investigating alternative ingredients, like black soldier flies and fungi protein, to replace more expensive fish meal. Plant-based ingredients in aquaculture feed are also common. Said Deng, “Plant ingredients like corn and soy have been in research for decades.”

Deng formulates feed for fish raised in aquaculture systems, such as these fingerling lake sturgeon. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Deng is currently experimenting with a new plant ingredient, alfalfa, which is a common forage crop for livestock like cows. She is researching whether the protein-rich plant could replace fish meal protein in the diet of rainbow trout.

While cheap, abundant ingredients are desirable, dietary changes shouldn’t negatively impact fish health, whether those fish are raised for food or for stocking purposes.

For example, Deng is working with Mole Lake Fisheries to develop a dry feed to replace the live minnows fed to walleye raised in outdoor ponds. Minnows are expensive, and while dry feed may be cheaper, walleye must be strong enough to be stocked in local lakes.

Deng must consider how the new diet impacts their long-term survival. “Can they run well in the lake?” asked Deng. “Can they survive? [Can they] still get used to catching live food?”

Working with fish farmers to develop a new feed or adopt a new technology is part of Deng’s work as an outreach specialist, but she also spends much of her time working with students—from high school to graduate-level. Some students seek out her lab because they love to fish; others just want to build their research skills. Deng then collaborates with students to tailor lab work to their interests or career goals. One undergraduate, Deng recalled, wanted to pursue dentistry, so she got creative.

“I asked him to look at different teeth of the fish to see the evolution of different food habits,” said Deng.

Deng holds up two yellow perch for two students who work in her lab. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

She has also worked with students interested in environmental law, public policy and communications and stresses that students don’t need to major in biology to work in her lab. “My goal is to open the window and the door to anyone who likes to learn,” she said.

And that includes the public. Deng offers educational tours of her lab to schools and community groups where participants learn more about aquaculture and get the opportunity to see tanks of juvenile sturgeon or eyelash-sized yellow perch. It’s a popular event, one that has inspired students to pursue working in her lab.

“You have to let the public learn what we are doing,” said Deng. “If you always close the door, then why are we here?”

Those interested in scheduling a tour of Deng’s lab should reach out to dengd@uwm.edu. Deng will also have open lab exhibitions at Harbor Fest in Milwaukee on Sunday, September 24, 2023.