What did you do this summer?

A red toy buried in sand at Bradford Beach. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

It’s a question that, in the middle of August, might prompt panicked reexamination of how you spent the long, warm days of a fleeting season. For Wisconsin Sea Grant’s Summer Outreach Opportunities Program scholars, the answers come easily.

This summer, 12 undergraduate students from across the country spent a jam-packed 10 weeks collaborating with outreach specialists on coastal and water resources projects across Wisconsin. Scholars conducted research, engaged kids and adults and shared the stories of Great Lakes science, all while working alongside mentors to explore careers and graduate education in the aquatic sciences.

Whether they wrangled fish in Green Bay or researched green infrastructure in Ashland, scholars have much to share about how they spent their summers. Here’s the first snapshot of four projects.

Project: Beach Ambassador Program for Great Lakes Water Safety

When Alan Liang and his fellow beach ambassadors push their powder-blue cart across Bradford Beach in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, curious beachgoers often approach with a question: What are you selling?

Alan Liang pushes the beach ambassador cart as he starts a shift at the beach. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Liang explains they’re not peddling cold treats. The brightly colored cart is filled with pamphlets about beach safety, not paletas, and the team is working to build awareness around the changeable water conditions of Lake Michigan.

“Our mission is to spread information as educators about how to keep yourself safe on the beach since there are no lifeguards,” said Liang.

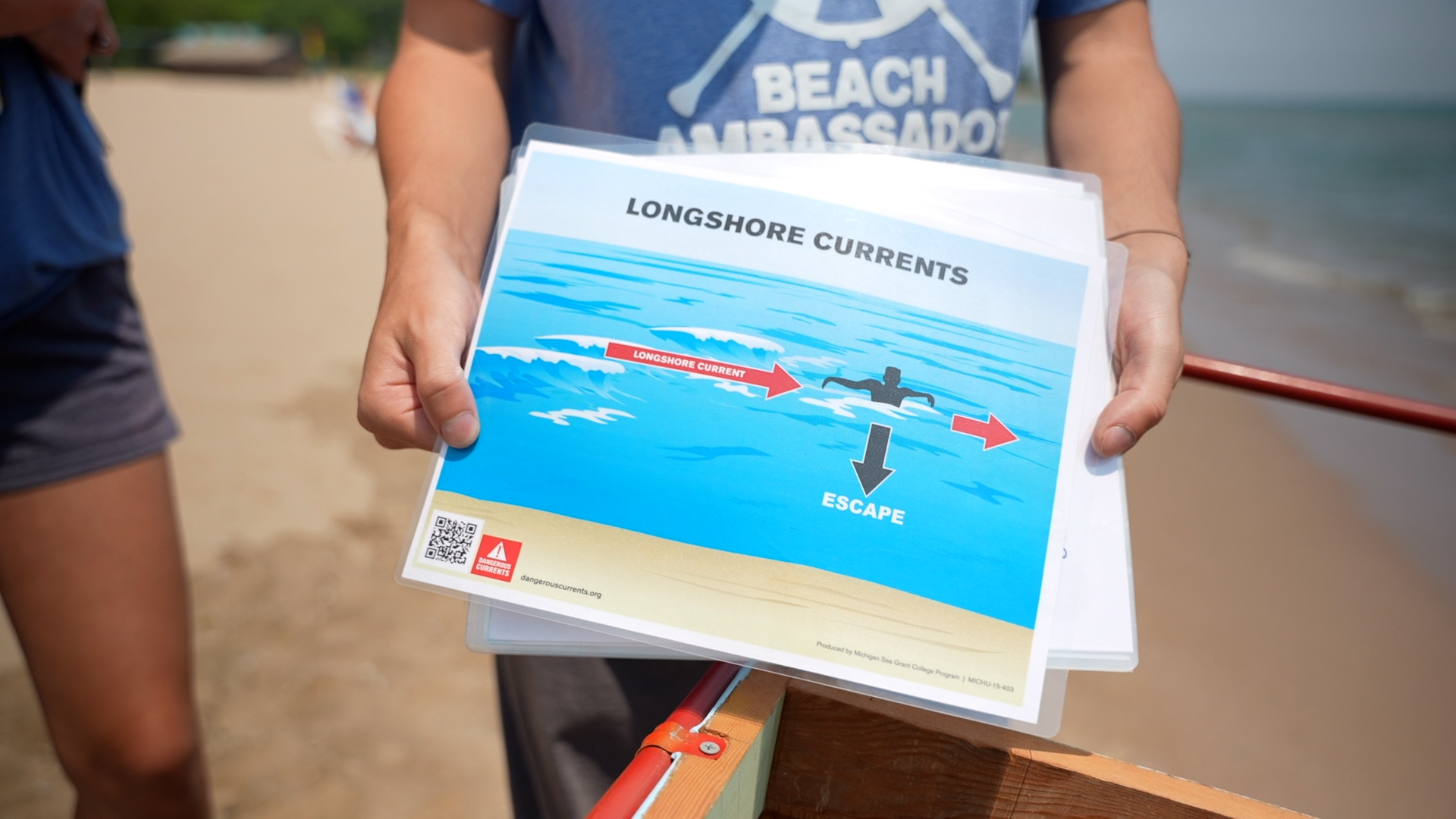

A collaboration between Wisconsin Sea Grant and Milwaukee-area partners, the Beach Ambassador Program began in 2021 in response to an increased number of drownings at Milwaukee beaches. Ambassadors, like summer scholar Liang, are trained to share water safety information with the public, including how to properly wear a life vest, escape a rip current, recognize water quality conditions and determine whether it’s safe to swim. Social Science Outreach Specialist Deidre Peroff serves as one of the program’s mentors.

Weather permitting, ambassadors rove the beach Thursdays through Sundays and begin each shift by gathering at their “shed” on the beach. The team then records the weather and water conditions for that day on a whiteboard: wind speed and direction, water temperature and quality and UV index. Those data then inform the conversations ambassadors initiate with beachgoers.

“For example, yesterday we had very strong winds from the northeast, which would generate a lot of longshore currents,” said Liang. “So that’s what we would talk about because that was the big concern for that day.”

Liang, a sophomore at UW–Madison majoring in computer science and environmental studies and a former math tutor, was drawn to the program because he likes teaching. “I wanted to do something a little bit more education-based, and I thought this was a great fit for me because I’ve also spent a lot of time around water.”

Approaching people, however, can be difficult. It helps that beach ambassadors move as a group, but Liang said this summer has challenged him to get outside of his comfort zone. “I feel like I’ve learned to overcome those awkward, uncomfortable situations,” said Liang.

A beach ambassador holds a factsheet about longshore currents. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Not all outreach happens near water. In addition to pulling ambassador shifts at Bradford Beach, Liang tabled at the Green & Healthy Schools Conference and talked with other Milwaukee-based, environmental justice-focused organizations. The goal is to connect with more audiences. “This helps to promote beach safety among those who may be hesitant to go to the beach at all,” said Liang.

He is also designing a website for the program that will launch in early fall. He likes that the project melds both of his interests and shows a possible path forward in both the environmental and computer science fields.

Although the future is on his mind, Liang is also enjoying the present moment, spending the summer along Lake Michigan in his hometown.

“It’s nice to just be where you’re from and interact with the people from your community.”

Project: Restoration and Monitoring of Coastal Habitats

Isabelle Haverkampf and Gweni Malokofsky spent their summers the way many of us wish we could: on the water. Under the mentorship of Fisheries Specialist Titus Seilheimer, Haverkampf and Malokofsky have been working on multiple projects in the Lake Michigan watershed, including surveying fish and manoomin (wild rice) in Green Bay and collecting water quality and site assessment data at Forget-Me-Not Creek between Two Rivers and Manitowoc.

Isabelle Haverkampf releases a fish back into the water. Photo credit: Isabelle Haverkampf

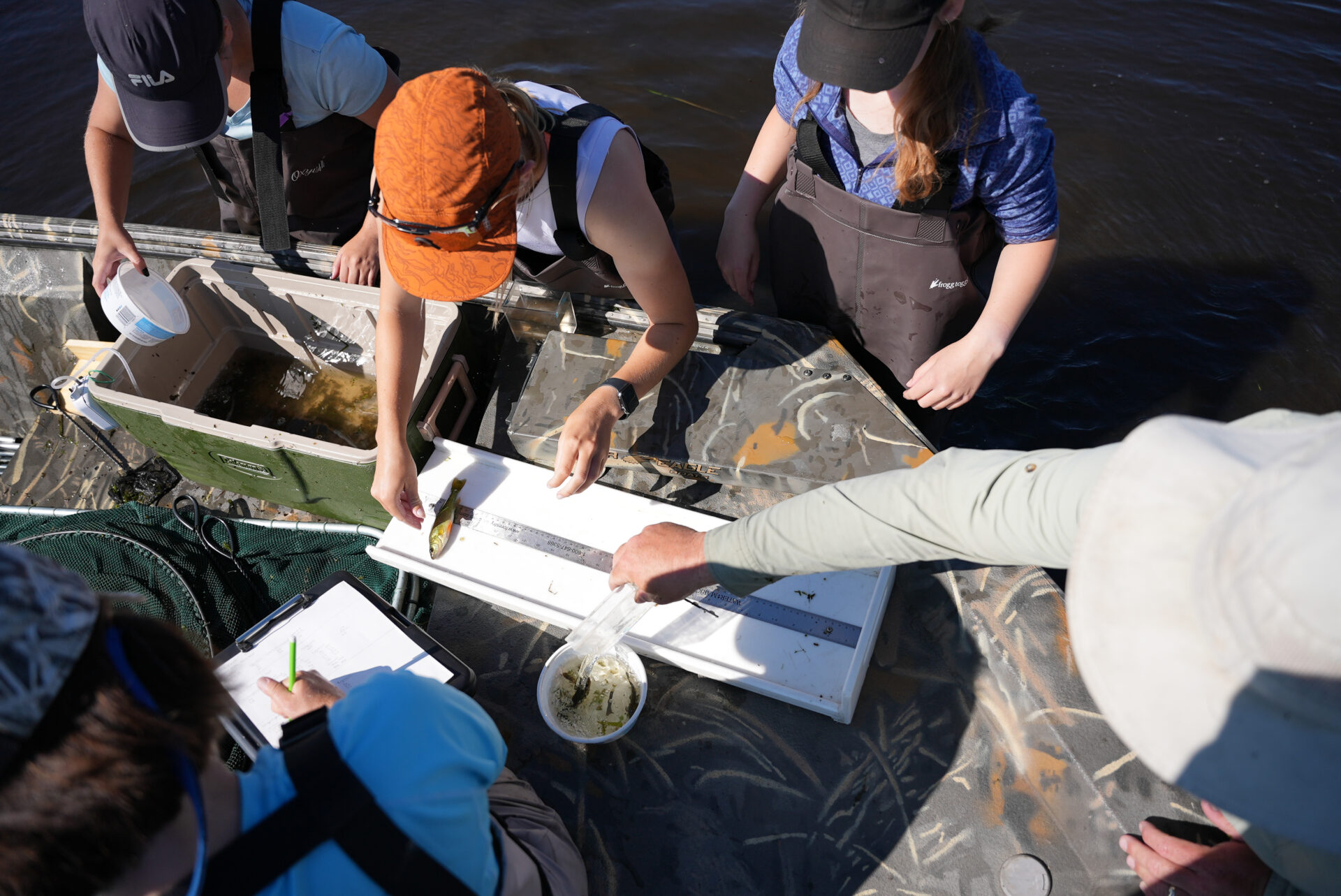

A highlight of the summer was fish monitoring. For one week each month, the scholars worked with partner organizations at four sites in the bay of Green Bay in Lake Michigan, setting fykes and hauling seine nets to collect data on the species, size and number of fish caught. Prior to this summer, neither had much experience handling fish.

“I was uncomfortable holding and measuring bigger fish at the beginning, but I’ve definitely gotten much better at it,” said Haverkampf.

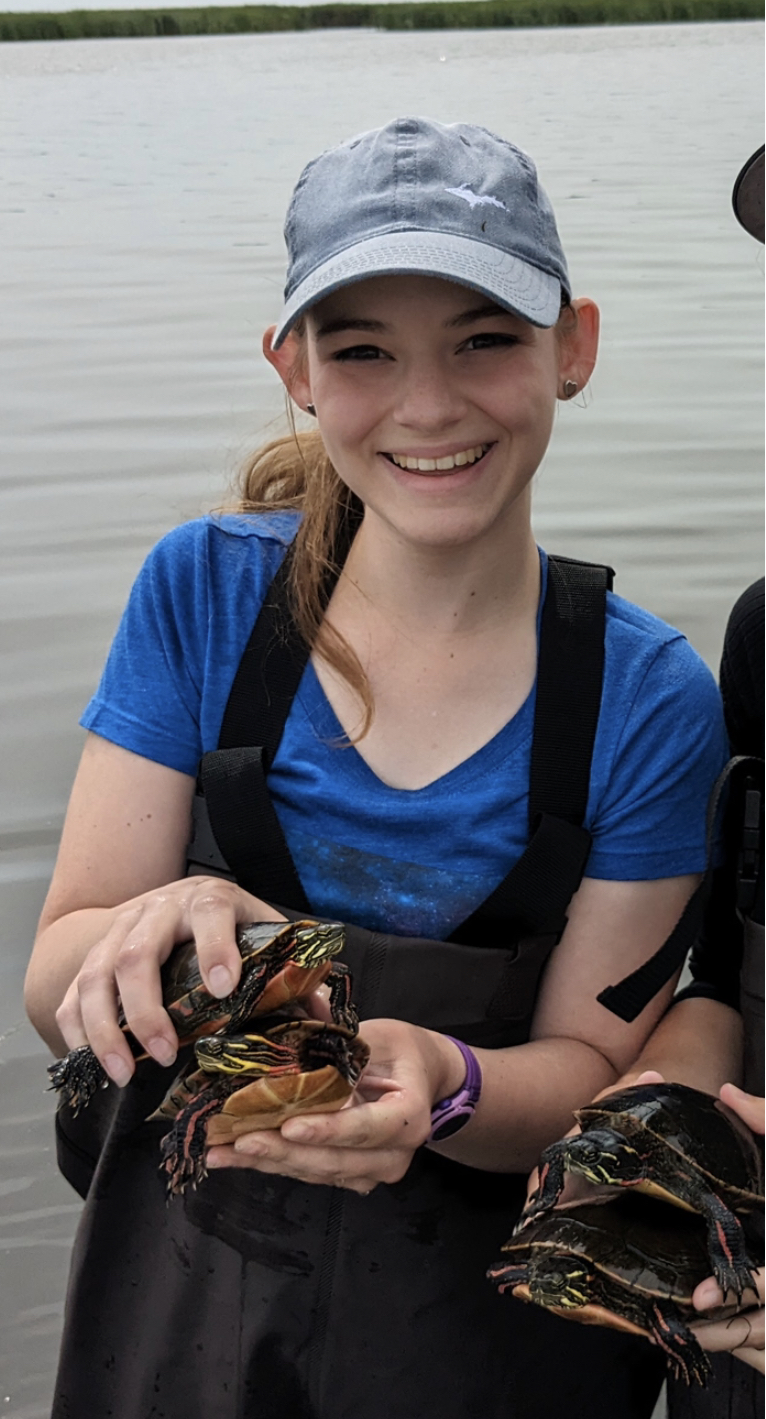

Gweni Malokofsky holds painted turtles she encountered during fish monitoring. Photo credit: Gweni Malokofsky

Together, the team netted banded killifish, yellow perch, gar, bowfins and bullheads. Some species, Malokofsky learned, were more cooperative than others.

“The bowfins are definitely the hardest to deal with,” Malokofsky said. “If they don’t want to sit there, they won’t.”

Overall, the experience affirmed the scholars’ interest in working in the natural resources field. Haverkampf, a water science and geology double major who will graduate from Northland College in December, gained clarity about what she wants to study in graduate school.

The team measures a fish. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

“I’ve found I really want to go into the water sciences sector, specifically in restoration or resource work,” she said, adding that she’s interested in how contaminants move through aquatic food webs.

Malokofsky, a sophomore at UW–Green Bay majoring in biology with an emphasis in ecology and conservation, appreciated the hands-on introduction to field work.

“I’m glad that I’m learning how to use different kinds of probes and tools and field equipment I previously haven’t had experience with,” she said.

Another perk of the experience? Knowing the best places for a peaceful paddle. Malokofsky said her family just got kayaks and canoes this summer. “Now I know some places I’d like to take them to.”

Project: Harvesting Manoomin as a Climate Adaptation and Resilience Strategy

This summer, Elliot Benjamin and Lucia Richardson immersed themselves in the stories and science of manoomin, also known as psiŋ or wild rice. Manoomin is an important food source with cultural and spiritual significance to the Native nations of the Great Lakes region but has been declining in range and abundance. Working with Social Science Outreach Specialist Deidre Peroff and partner organizations in Minnesota, the scholars participated in field work, field trips and independent study to learn how manoomin is connected to human, plant and animal communities and how those connections can help the plant thrive—despite changes in climate, water quality, land use and hydrology that threaten its existence.

Summer scholar Elliot Benjamin. Photo credit: Elliot Benjamin

For Benjamin, a senior at Marquette University majoring in sociology and gender studies with a minor in English, this summer was an opportunity to take a deeper dive and learn more about the ecological importance of a plant they first encountered in a Native American literature course.

“I knew some of the cultural significance and had read a little bit on my own,” said Benjamin, “but I didn’t know a lot about the biology of the plant itself and the history of the Anishinaabeg culture and all the different factors that are harming [manoomin].”

Summer scholar Lucia Richardson. Photo credit: Lucia Richardson

Richardson, a junior at Northland College majoring in nature and humanities with a minor in Native American studies, was also familiar with manoomin, having made rice knockers and participated in harvesting. This summer, she learned more about the relationships between manoomin, water quality, wildlife and the overall ecosystem.

“Manoomin is a keystone species,” said Richardson. “Manoomin in a habitat means that it’s a healthy, thriving habitat.”

Both scholars worked on capstone projects that raise awareness of the plant but also foster relationships between people.

Benjamin wrote an essay blending what they’ve learned about manoomin with reflections on their identity as a trans person.

“I wanted to take a more personal reflection approach to it,” they said, noting the capstone was a good opportunity to tap into their training in the humanities. Benjamin plans to submit the piece to an academic journal currently seeking papers about trans perspectives and ecology.

Richardson built upon an oral history project she began at Northland College transcribing and digitizing interviews with Bad River and Red Cliff tribal elders and government officials. Recorded in the 1970s, the oral histories were recently found on cassette tapes in the Northland Indigenous Culture Center and feature both personal and tribal history. Richardson is returning the tapes to tribal governments and hopes to collaborate on a future project.

As humanities students, Benjamin and Richardson appreciated how the summer exposed them to scientific topics and field work while welcoming their perspectives as nonscientists. Both are considering futures in environmental studies. Said Benjamin, “[The summer scholar experience] made it feel more attainable.”

Project: Environmental Video Production

Van Mill out in the field. Photo credit: Bonnie Willison

Jeremy Van Mill knows that observation is a good teacher—a lesson his summer scholar experience has helped him appreciate in a new way. Alongside video producer Bonnie Willison, Van Mill travelled across Wisconsin filming and photographing Sea Grant-funded researchers, outreach specialists and fellow summer scholars in the field. With no formal training in the aquatic sciences, Van Mill learned by watching and listening with his camera.

“One of the things I really enjoy about this position is that I am exposed to topics that I don’t have any experience with,” said Van Mill.

Van Mill, a second-year student in visual communications at Madison College, profiled the work of Aquatic Invasive Species Outreach Specialist, Scott McComb, and edited a video about groundwater flooding research on Crystal and Mud lakes in Dane County. He also edited the audio for a live performance of “Me and Debry,” a Sea Grant-funded play about marine debris, and photographed numerous events and outings.

The experience invited Van Mill to practice different ways of telling stories and producing videos. “It’s forcing me to stretch and change and reconsider the way I do things,” he said.

One of Van Mill’s favorite moments he captured this summer: Titus Seilheimer and a little, whiskery brown bullhead. Photo credit: Jeremy Van Mill

For example, letting the footage shape the story. In his previous film projects, Van Mill knew exactly what he was getting into: with script in hand, location scouted and actors rehearsed, he could plan out every shot in advance. That sort of control isn’t possible when filming in a poorly lit laboratory or on a boat in Lake Michigan, especially if your subjects move in unpredictable ways.

“You have to take a step back a little bit and stop trying to stage things or control different elements and seize the opportunities you have,” said Van Mill.

That means being present, paying attention and letting the story unfold on its own. “You’re sort of like a fly on the wall more than you’re producing video,” said Van Mill.

Van Mill’s macro photography captures small creatures up close, like this butterfly. Photo credit: Jeremy Van Mill

Speaking of flies, Van Mill films them, too. While in college, he started dabbling in macro videography and photography, meaning he films very small things. His subject of choice? Insects. Van Mill has spent hours finding and filming various critters going about their insectile agendas on beaches and in backyards.

“I learned a lot about insects by observing them,” said Van Mill. The videos reveal details people don’t usually see, like the tiny hairs on a fly’s leg or the coiling proboscis of a butterfly.

So much of the world opens up when you pay attention. Van Mill said it best: “Everyday things become extraordinary with a different angle or different perspective.”

***

Be sure to read part 2 as well.