A few years ago, Gene Clark, Wisconsin Sea Grant’s coastal engineer, got a call from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) about a problem. Residents of Madeline Island in Lake Superior were complaining that a neighbor’s pier seemed to be causing erosion to their beaches. The DNR wanted Clark to come to the island and take a look.

That the DNR would turn to Clark for objective advice is not uncommon. “If the DNR has an issue or a significant erosion control project that somebody wants to do, they often ask me either to look at the plans or to go out with them to the site,” Clark said. “That’s what this was.”

The conditions were evident to Clark right away. “There was a definite buildup of sand on one side of the pier, and a significant deficit on the other side,” Clark said. After doing some more research, he learned that the problem probably started even before the current owners bought the property. They inherited a dock and a concrete pad built for a commercial fishing operation. The structures interfered with the natural dispersal of sand along the beach.

The problem was intensified when the owners, Philip and Terri Myers, added onto the structure under a permit issued by the DNR in 2001, until they had a “significant private property dock with portions of the old one still in place,” Clark said.

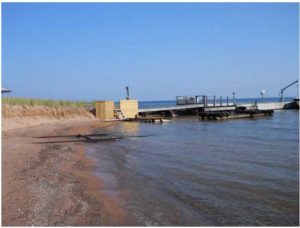

The Myers Family pier structures on Madeline Island. Image credit: Gene Clark, Wisconsin Sea Grant

“Some of my conclusions were that the entirety of the group of structures were making a difference on the down-drift side. It was difficult to pull out how much of that was attributable to the portion that the current dock owner built because there’s still remnants of the old structure,” Clark said. “But clearly the combination of all of the changes were making a difference.”

Another issue was that the current dock had an opening that was too small, and behind it about 20 feet were remnants of another dock that were blocking the flow of sand so that it quickly piled up. One neighboring property owner said he had lost about 80 percent of his beach. Another called Clark in tears because her former large beach was now nothing but a five-foot embankment.

A storm had damaged the pier and the Myerses wanted to make it more solid and larger. In cooperation with the DNR and Philip Myers, Clark worked on design ideas that would allow the dock to be sturdier, yet make it more permeable so that sand could travel naturally down the beach to the neighbors’ properties. Myers did not agree to the eventual plans, so the DNR denied him a permit for reconstruction.

Myers took the case to the Wisconsin Court of Appeals District 3. Citing Clark’s information in three instances, the court ruled against Myers, noting that his reconstruction plans would cause increased shoreline erosion for his neighbors.

Myers then took the case to the Wisconsin Supreme Court. After reviewing briefs filed by the DNR and Myers, on January 18 the court ruled in favor of the Myers, saying that the DNR did not have the authority to amend the Myers’ permit granted in 2001. This effectively reversed the court of appeals decision.

In their decision, the justices cited Clark’s report, honing in on his expert view that it was “extremely difficult to estimate how much if any additional littoral material trapping is occurring due only to the [Myers’] newer pier structures.”

The justices contend that the dock permit is akin to a building permit, which can no longer be modified after construction is complete after the time period specified in the permit. In this case, it was three years. They said that although “The DNR possesses a limited right to modify a permit until the earlier of the expiration date of the permit or the date when pier placement was completed . . . that right does not include the ability to require partial removal of a pier, and substantial modification to a permit, over 14 years after a pier was placed.”

In effect, the Myers’ permit expired, so the DNR could not require modifications to their pier.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Ann Walsh Bradley argued that piers are not like buildings because they are constructed in the more dynamic environment of water rather than the more static element of land. She thinks the pier-permitting statues give the DNR the right to amend permits and set forth a continuing obligation to meet the permit requirements.

“The question raised in this case is what happens when a pier meets the criteria of [state statutes] when it is initially installed, but at some point conditions change and the pier no longer meets the statutory requirements,” Bradley writes. “The statute dictates that if the requirements are not met, then a permit shall not issue. This means that the non-compliant condition must be corrected.”

She said the court’s decision renders the DNR “toothless” to fix similar situations where a pier is not functioning properly, “even if it obstructs navigation, is a detriment to the public interest, or reduces flood flow capacity.”

The Myers Family pier after storms destroyed much of it. Image credit: Gene Clark, Wisconsin Sea Grant

This fascinating case has gone as far as it can, for now. Whatever the decision, Clark said he was satisfied that the courts and the DNR used his expertise to make their arguments, in line with Wisconsin Sea Grant’s role as a purveyor of evidence-based information.

While the case was going through the courts, natural coastal processes continued in Lake Superior. Several more storms destroyed much of the pier. So although this case may have a long-lasting impact on the way the DNR manages permits, the structures that raised the issues are no longer functioning.

The lake, it seems, issued the final verdict.